Chile’s Socialist Turn

By all economic and social accounts, Chile has been the most successful Latin American country of the last generation.

Since the mid-1970s, the country’s gross domestic product has quadrupled in size, and its poverty rate has fallen from 45 percent to just 9 percent. Since the 1990s, its extreme poverty has fallen from 35 percent to just 2 percent, the middle class has grown from 23 percent of the population to 65 percent, and the country’s life expectancy has increased from 69 to 79 years of age.

Moreover, 85 percent of Chileans between 25 and 34 years of age have secondary education, which is over ten times the number of students in higher education that Chile had in the 1970s. Overall, the United Nations’ Human Development Index has Chile as their highest-ranked country in Latin America, among the fifty highest-ranked countries in the world.

For these reasons, all of us in Latin America had Chile as an example for the region. A country that found a way to achieve political, social, and economic stability, which is something that virtually all Latin American countries have lacked throughout our history. A situation that Bolivar called two centuries ago when he said that the region seems to be inevitably destined to “fall into the hands of rampant crowds, and then into the hands of tyrants so insignificant that they will be almost imperceptible, of all colors and races.”

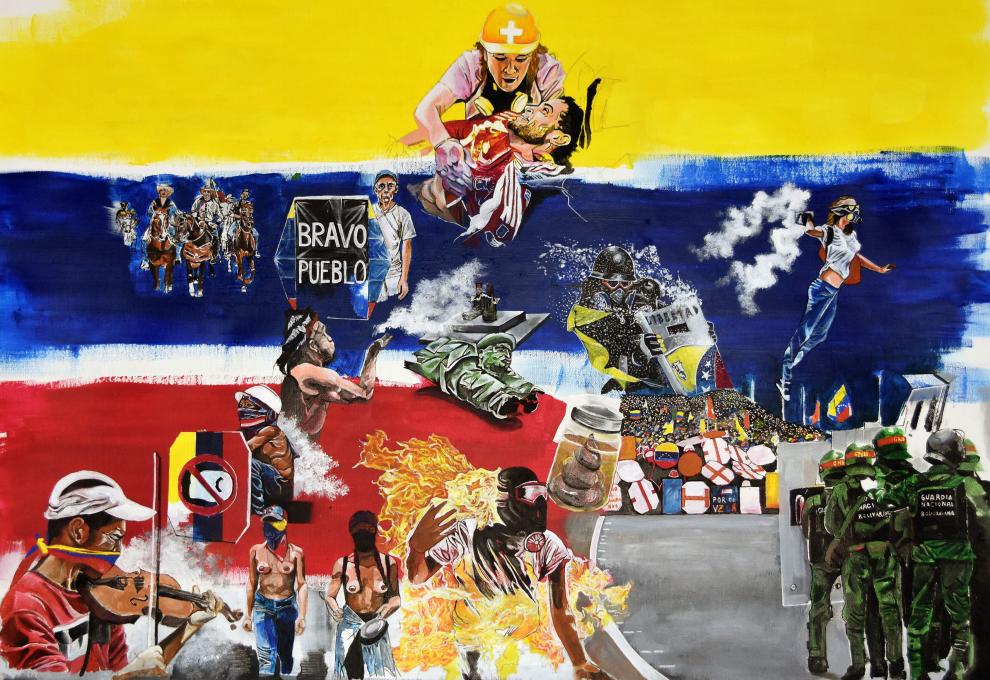

However, Chile’s success story came officially to an end in 2020, when 79 percent of Chileans voted in favor of drafting a new constitution for their country. A process that has recently taken place in countries like Venezuela, with less than stellar results. For two reasons. first, as a result of the high levels of uncertainty that constitutional processes create; and secondly, as a result of the people actually writing the constitution.

On the second point, it is astonishing to see how are socialist the people in charge of writing the new constitution. From proposing the nationalization of big economic sectors to the collectivization of Chile’s pension funds, the newly elected lawmakers in Chile have not been shy to express their socialist ideas and plans for Chile.

In fact, the right-wing coalition in Chile (lead by Chile’s President Piñera) only won 37 of the 155 seats of the constitutional convention, which is not even enough to veto any proposal at the convention (as a veto would require 52 seats or 1/3 of the convention).

The remainder 118 are composed in the following way. The old left, mainly composed by social democrats, got 25 seats. The radical left (compromised of the Broad Front and the Communist Party) won 28 seats. The independents won 48 seats of the convention. According to America’s Quarterly, most of them “are left-wing community organizers, and activists of traditional left-wing causes, including environmentalists, feminists, public housing advocates and community organizers.” And lastly, 17 seats will go to in indigenous groups, most of them also identified with socialist causes (according to America’s Quarterly as well).

For this reason, it is safe to assume that Chile’s new constitution will not just be at the left of its current constitution. I would argue that the new constitution will go even to left than most Latin American constitutions, which are already very socialist at their core.

This is sad because it will mean the end of Chile’s period of economic growth. And no, I’m not being overly dramatic. The direction that Chile is taking is worrisome, to say the least. It will create a new constitution in which the state will have too much power in matters related to the economic activity of the country. And as such, Chile will become more like the rest of the region.

In conclusion, this has been a black month for Latin America. With Chile’s suicide and Colombia’s madness, I am afraid for our future as a region. Perhaps, Bolivar was right, and we are destined to fail.

By Jorge Jraissati

Jorge Jraissati is the president of the Venezuelan Alliance. Graduated at the Wilkes Honors College, Jorge is an economist, political leader, and a fellow at the Abigail Adams Institute. Jorge has been invited as a guest lecturer to over 20 universities, such as Harvard, NYU, and Cambridge.