COVID has Strengthened Authoritarian Regimes Around the World

This essay discusses the political consequences that the pandemic has brought to countries under authoritarian regimes, such as China, Russia, and Venezuela. For these regimes, the pandemic has not been a source of concern but of strength, serving as an excuse to arrest journalists, increase surveillance over civilians, and militarize entire cities.

For democratic governments all around the world, the COVID-19 crisis has been the main issue of 2020. In the European Union, for instance, the pandemic has compromised its public healthcare system, and the well-being of its population, especially considering that roughly twenty percent of Europeans exceed 65 years of age.

Beyond public health concerns, democracies have also been suffering the economic consequences of the pandemic and its lockdowns. In the case of the Trump administration, the United States economy shrunk by 3.5 percent in 2020, and the U.S. budget deficit rose by $3 trillion.

And from a diplomatic perspective, the pandemic has also raised doubts about the desirability of our international order, for instance, by making apparent the risks of China’s influence, as well as the lack of effectiveness of international organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO).

Yet, for authoritarian regimes, the situation could not have been more different. For them, the pandemic has not been a source of concern, but of strength. Because in countries like Russia, Venezuela, and China, the pandemic has served as an excuse to arrest journalists, increase surveillance over civilians, and militarize entire cities.

In Russia, for instance, the pandemic allowed the Putin administration to increase civil surveillance. If a Russian is “suspected of infection,” he or she has to install a tracking software on his or her phone. In Moscow, the government also installed roughly two hundred thousand cameras with facial recognition. And in other regions of Russia, all citizens who want to move in public spaces have to download a QR code to their devices. These are measures allegedly applied in the name of public safety. Yet, in September, the government allowed 30 thousand spectators to attend its Formula 1 Grand Prix, celebrated in Sochi.

Beyond civil surveillance, the pandemic has also allowed authoritarian regimes to censor free speech in their respective countries. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán secured an indefinite state of emergency, enabling him to rule by decree and imprison journalists who disseminate “false news.”

In a panel held at the Macmillan Center of Yale University, Dr. Aniko Szucs argued that these actions have not only strengthened Orbán’s image as a “paternalistic and authoritative figure” but also allowed him to turn Hungary’s “illiberal democracy into a dictatorial regime.” Professor David R. Cameron added that the pandemic has in some countries “resulted in an erosion and weakening of democratic norms and practices,” and in others has “reinforced and strengthened their reliance on authoritarian politics.”

This has become noticeable in the Philippines, where President Rodrigo Duterte has threatened to reinstate martial law to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. Among Duterte astonishing statements, he has threatened with directing the army to go into people’s houses, so they can identify infected people, and interrogate citizens about neighbors not respecting the lockdown. President Duterte has even said that he “will not hesitate to ask the army to shoot.”

Similarly, since the beginning of the pandemic, the Chinese government has imprisoned and repressed numerous doctors and journalists who were alerting the world about the situation in Wuhan. To illustrate, there is the case of Zhang Zhan, a lawyer who posted videos of Wuhan at the start of the pandemic. She was arrested in May; and last month, she was formally indicted on charges of spreading false information. If she is convicted, she will face up to five years in prison; she is currently on a hunger strike.

Besides the case of Zhang Zhan, several other Chinese citizens have disappeared for reporting on the pandemic, such as the cases of Chen Qiushi, Fang Bin, and Li Zehua. This information is also confirmed by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). In its annual global survey, the committee found that China this year jailed more journalists than any other country. It also found that, worldwide, an astonishing 274 journalists were jailed in 2020 because of their work, marking the fifth consecutive year with more than 250 journalists imprisoned by authoritarian regimes.

China’s case is not only the worst in magnitude but also the most frustrating of all, considering that the free flow of information from Wuhan could have helped the world to address the pandemic in a more effective manner. As I wrote back in August, “[China] could have alerted other nations earlier. It could have stopped all flights from Wuhan earlier. It could have told the truth about its number of cases. And while I am not arguing that China could have prevented the virus by itself. It could have acted responsibly, potentially saving thousands of lives, millions of jobs, and trillions of dollars. It simply chose not to do so.”

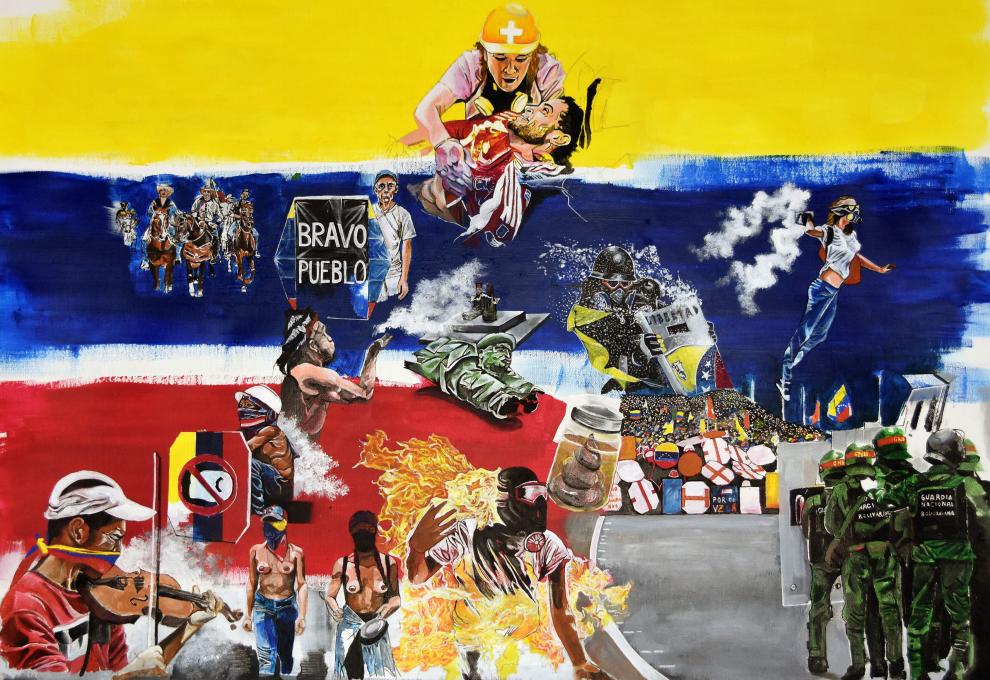

And lastly, the pandemic has also strengthened authoritarianism in my own country, Venezuela. Since day one, COVID has allowed the Maduro regime to consolidate its grip on power. As I wrote in April for Public Discourse, the pandemic has been used by the Maduro regime to excuse himself of all kinds of abuses. For instance, since mid-March, Venezuela has followed extremely rigid quarantines, with the military spread in every corner of the country. Accordingly, the military is in charge of monitoring the sanitary measures of businesses. And as usual, instead of using their power with responsibility and honesty, they have used it to blackmail business-owners and to favor businesses owned by friends of the regime.

Moreover, the pandemic has also weakened the Venezuelan opposition by shifting public opinion away from the political crisis of the country. Domestically – since the opposition cannot protest or organize itself, and journalists are not allowed to report on the humanitarian crisis of the country – most of the public opinion has revolved around the COVID-19 crisis, and not around finding solutions to the political crisis of the country. A similar situation has occurred beyond Venezuela. While the year began with Juan Guaido doing an international tour – which ended with him being mentioned at Trump’s State of the Union – as the year went by, the international community forgot about Venezuela, and rationally focused on addressing the worldwide pandemic. For these reasons, 2020 turned out to be a lost year for the Venezuelan opposition, and time is not in their favor.

An Authoritarian Future: Not an Inevitable Outcome

Despite the political gains of these authoritarian leaders, authoritarianism is not an inevitable outcome for these countries. But to assure a future of democracy and freedom to these people, all of us have to work towards that goal. In developed nations, with a free press and strong civil institutions, citizens have to use their influence to empower their repressed counterparts.

This can be done by raising international awareness about the human rights violations that take place in nations under authoritarian rule, so that NGOs, multilateral organizations, and democratic governments are encouraged to pressure these regimes for their abuses. This tactic is proven to be especially useful among illiberal regimes. In these countries, while authoritarian leaders have successfully constrained electoral competition and institutional oversight, their governments still have some degree of international and domestic accountability.

In synergy with raising awareness, the democratic world and its institutions have to work on strengthening the civic institutions of these illiberal countries, so they can reverse their current authoritarian trend. For instance, greater censorship to independent journalists should be replied to with greater international coverage of the situation, legal support for the victims, and resources for their work.

Lastly, the ultimate action that the democratic world can do to honor those without freedom and democracy is to protect our democracies, especially our most influential democracies. This year, we just experienced – at a global scale – the risks of having powerful and influential authoritarian regimes. Because as I mentioned, if China were to be a democracy, maybe with a free flow of information and diplomatic cooperation between nations, the world could have contained the virus before it was too late.

For this reason, among the many lessons that 2020 taught us, one of them is the importance of keep pushing towards a freer and more democratic future for all our nations.

By Jorge Jraissati

Jorge Jraissati is a Venezuelan economist and the president of the Venezuelan Alliance, an international non-profit that explains the causes, analyses the consequences, and brings about solutions to the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis. Jorge has spoken on this issue at universities like Harvard, NYU, and Cambridge