From Despair to Guaidó: How the Opposition Took Power in Venezuela

Despite what some would have you believe, Guaido's assumption of power in Venezuela was not the work of one wizard, operating behind the scenes.

"This story was the result of consulting with several sources that prefer to remain anonymous and not be cited."

In August 1943 the early stages of the famous Operation Overlord were plotted. It was the capture of the Bastille, or the assault on the Winter Palace, of the Second World War. The great plan that, despite unfavorable conditions, would tip the balance of power in favor of the Allies. In Venezuela, preparations for D-Day began in December 2018.

There is no Venezuelan Eisenhower-type leader; neither is there a Montgomery. Though some would have us believe otherwise, the great seizure of power in Venezuela was not plotted by a single individual, from his garden, in a Machiavellian manner. There were many voices that, in their spaces, articulated to the country – and to the world – the need to undertake the great political operation that today has Maduro in check. The tyrant is trapped in his führerbunker.

“The Constitution gives me the legitimacy to exercise the office of the President of the Republic to call elections…I adhere to Articles 233, 333, and 350 of the Constitution to achieve the cessation of the usurpation,” said then-deputy Juan Guaidó at noon on January 11, 2019.

Immediately after what was the beginning of the town councils, the first to recognize Guaidó as the new president of Venezuela was the secretary general of the Organization of American States, Luis Almagro. The speech to the town councils had been quite ambiguous, so Almagro practically affixed to him, with cement, the presidential band upon Guaidó.

But the night before quite a lot had happened. Twenty-four hours before the first council meeting, Juan Guaidó had no plans to cite Articles 233, 333, and 350 of the Constitution. He had no plans to say anything about the office of the presidency whatsoever.

We have to go further back; several weeks back, to when those responsible for the seizure of power in Venezuela, those who orchestrated the Caribbean invasion of Normandy, began to build the grand strategy that led to Juan Guaidó on January 23, 2019. The decisive moment in which, the bayonets were loaded, the ships were ready, the troops disembarked, and an irreversible process began. With the swearing in of Guaidó as interim president of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro entered the last period of his dictatorial mandate. Unalterable. Invariable. Definitive.

Preparations for D Day

Outside the Casa de las Américas, in Washington DC, it was about eight degrees celsius. It was December 14. It was a cloudy day. In the office of the secretary general coffee was served to the guests: they were the president of the Venezuelan Supreme Court of Justice in exile, Miguel Ángel Martín; the deputies Francisco Sucre, Freddy Superlano, Carlos Lozano, and Juan Guaidó. On speakerphone were Julio Borges and the great leader of the Popular Will political party, Leopoldo López.

They discussed what they all agreed was a unique opportunity. Never had such a convenient occasion been presented in twenty years of Chavismo. The region now favors change, with new heads of state, conservatives, aligned with the White House, which is now governed by a pragmatic entrepreneur, a staunch enemy of the global Communist movement. In addition, it was necessary to designate a new directive of the Venezuelan Parliament. It was time to move away from a leadership that had done a lot of damage to Venezuelan citizens and that today lacked prestige and credibility. But the most important thing, beyond the possibility of refreshing the political landscape in Venezuela, was the opportunity to depose Nicolás Maduro through a fully Constitutional process.

The discussions had been going on for months, it’s true. Four Venezuelan leaders who, in coordination with the main political players in South America, sought to establish a concrete path that would facilitate the fall of the Nicolás Maduro regime. They were María Corina Machado, Antonio Ledezma, Julio Borges, and Leopoldo López. But in December the first steps were taken – with the absence, and behind the backs, at that time, of two of the leaders. And then they began to flirt with the idea: to focus all efforts on a path, legitimate, Constitutional, that could be supported by the international community without the fear of being listed as accessories in a coup d’etat.

There was no consensus. It was just an idea floating in the air. Like a utopian fiction, it seemed too distant because everything depended on a National Assembly that had only been able to offer frustration to the Venezuelan people. But most of the actors, the sensible ones, those genuinely committed to the cause of freedom in Venezuela, saw in Article 233 of the Constitution the last great opportunity to overthrow Nicolás Maduro: whether they wanted it or not, the Nationaly Assembly had the responsibility. It was an obligation.

The plans were drawn. The team was assembled. The Eisenhowers emerged: two in Caracas, others in Washington, one in Bogotá and the other, in Madrid, began to outline the project. And part of the strategy was to press. Publicly and privately. Otherwise, the risk of the plan not being executed – or of being sabotaged by undercover enemies – was very high. You had to raise your voice.

On December 21, in a video posted on her Twitter account, one of the four, María Corina Machado, sent a message to the National Assembly of Venezuela. “We have a new opportunity,” she said. “We have to save the country.”

“Nicolás Maduro is an illegitimate president. On January 10 his presidential term ends and there will be no elected president in Venezuela. Period. There is a power vacuum, which must be filled by the National Assembly, designating a transitional government led by the president of the National Assembly itself,” Machado said on that day.

And the exiled Caracas mayor, another of the four, Antonio Ledezma, did the same thing on December 23: “Next January 5, more than installing a board of directors of the National Assembly, a transitional government must be installed. Because Maduro is illegitimate.”

Already public opinion was taking shape: the diplomat and former president of the Security Council of the United Nations, Diego Arria; the jurist and secretary of the IDEA group, Asdrúbal Aguiar; the prestigious Harvard professor, Ricardo Hausmann, all spoke out. The Secretary General of the Organization of American States, Luis Almagro, had cried urgently that with the prospect of a power vacuum on January 10th, the president of the National Assembly had a responsibility to act.

In the halls of power where these things are plotted and important decisions are made, the subject was still being discussed. The Organization of American States insisted on the route that looked like the most appropriate. Meanwhile, in the White House, hawks began to circle around Nicolás Maduro.

As regional leaders joined the opposition’s cause, ordinary citizens joined in as well. Keyboard warriors on social media took up the battle cry of Venezuelan freedom, and looked to Constitutional procedure. Fortunately the Constitution is quite clear. And in those days, it was quoted frequently.

The year ended. The people began to watch for what decisions National Assembly members would take with regard to the new directive. As there was already much discussion of Article 233, much depended on who would remain as president of the National Assembly. But an event, before the appointment of the new heads of the Assembly, captured everyone’s attention. It was a statement that marked a milestone.

Sources close to the process say that the declaration that the Lima Group gave on January 4 of this year surprised even the United States government. In the statement, it reads: “The Lima Group urges Nicolás Maduro not to assume the presidency, to respect the powers of the National Assembly, and to temporarily transfer power until new elections are held.”

That day, after a summit held in the capital of Peru, fourteen countries agreed not to recognize “the legitimacy of a new presidential term of the Nicolás Maduro regime that will begin on January 10, 2019.” It was forceful and transparent. The powers of the region, excluding Mexico – which did not subscribe to the text – and the United States, imposed a deadline. And, in addition, they referred openly to the project that had begun to be assembled in December: the President of the National Assembly would now be responsible for assuming the powers of the executive branch.

By this time there was still no consensus among the four political factions of the real opposition. Divided in two, one party was more inclined to the idea of a Council of State made up of those who were steering the three main legitimate institutions (the Assembly, the Tribunal and the Prosecutor’s Office); and the other, always more radical, and allergic to anything that had to do with dialogue or elections, remained firm in the idea of subordinating itself to Article 233 of the Constitution. These two, along with the other planners of Operation Venezuelan Overlord, came out emboldened with the agreement signed on January 4 in Peru. “The United States applauds the Lima Group for taking the side of democracy in Venezuela and denouncing the next illegal inauguration of Nicolás Maduro. The elections in Venezuela were flawed and unfair,” said US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

On the other hand, the declaration of the Lima Group generated an attack by those whose interests were threatened. They completely underestimated the idea of a new president in the country – and they suggested that it would unleash violence, persecution, and more confrontation.

Many meetings, and encounters. Calls. Applications of pressure. The world already saw, right in front of itself, its opportunity to get rid of Maduro. They were not going to let it happen. And it was disturbing that there was still discord among those who had to agree to advance the seizure of power in Venezuela.

As desired, Juan Guaidó was appointed president of the National Assembly. Despite a political agreement that was reached in 2015 when the opposition won the National Assembly, there was anguish over the possibility that discredited parties might sabotage the pact that gave Popular Will the presidency. Fortunately, nothing of this nature took place. The political forces aligned with Leopoldo López obtained the votes and elected Guaidó to what would emerge as the most powerful position in the country.

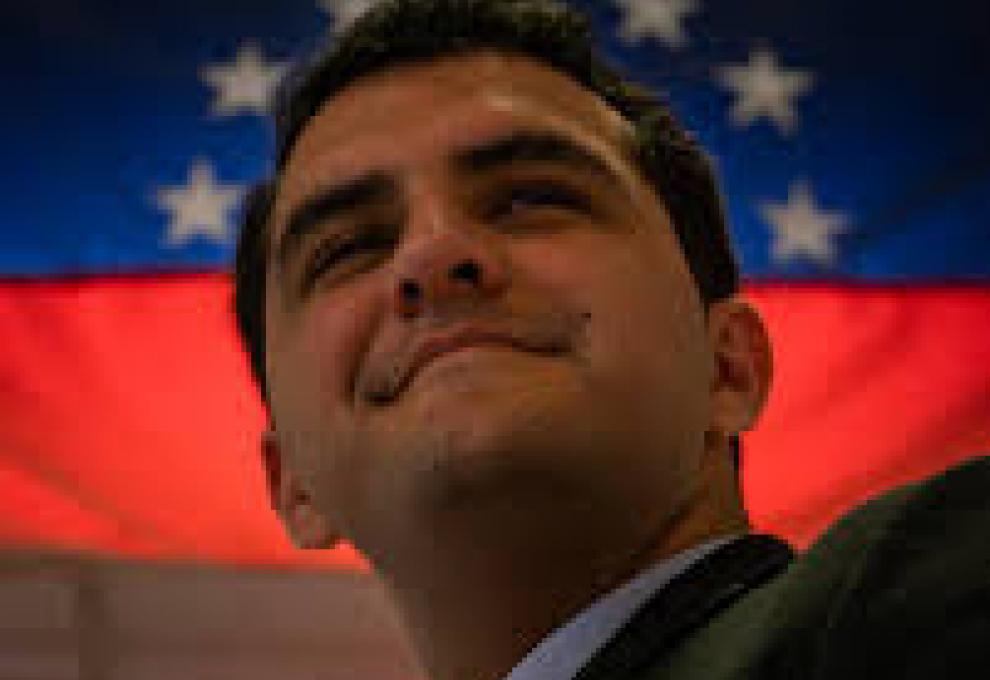

As those who dealt with him during the preparations for the D-Day would attest, Guaidó always had the will to assume the risks inherent to the historical position that he now assumed. Of all the deputies, he seemed the right person for the responsibility. Young, blameless, and energetic. With slow but precise rhetoric. Elegant, virile, with a model family. He was the right man for the right time.

At 12 o’clock on the night of January 10, the diplomat Diego Arria posted a message on his social networks. “As of this moment, the president of the National Assembly, the deputy Juan Guaidó, has become the president in charge of the Republic of Venezuela…it is his obligation…I know it is a difficult decision…I say to the new president, if he is sworn in, I am willing to lend him all manner of assistance…Congratulations!” Arria said. A statement that immediately went viral. He was the first to adhere to the presidential camp, and also the first to mention the urgency of a swearing-in and the idea of appointing ambassadors in countries that recognize Guaidó as president.

But the new president of Venezuela seemed unaware that, on his shoulder, now hung Venezuela’s tricolor sash. Given the illegal inauguration of Nicolás Maduro on January 10, of which there is nothing important to note beyond the fact that it was a shameful display of the world’s abandonment of the Bolivarian Revolution, Juan Guaidó gave a speech at the headquarters of his party: Popular Will. It was silly and badly structured. He insinuated that he was not going to assume the presidency of the republic. Instead of discussing what was rightfully his mantle to claim: as Commander-in-Chief of the Bolivarian National Armed Forces, he ended up announcing that there would be no announcement that day, but that there would be one the next.

The weight of public opinion prevailed as never before. The Venezuelan society is not the same one that enjoys pandering to imprudence. He went out with everything to make the complaint that something bad was happening. In parallel, the sword of Damocles hung over the proceedings like a warning that, if Guaidó evaded his responsibility, the other legitimate institution, the Supreme Court of Justice in exile, would be willing to appoint a transitional government. Sources close to the magistrates assured that everything was ready to respond to the possible decision of Juan Guaidó not to adhere to Article 233 of the Constitution.

“Justices of the Supreme Court of Justice met with the Secretary General of the OAS. They spoke with urgency of complying with Article 233 of the Constitution of Venezuela so that there was no vacuum with respect to executive power,” was posted on Twitter, along with a photo of the magistrates in Almagro’s office, on the Twitter account of the Supreme Court of Justice in exile.

The day was long. Very long. From early on television commentators said that it seemed that the deputy of the National Assembly was shirking his responsibility. On NTN24 the writer and Georgetwon University professor Hector Schamis, said that Guaidó had the choice of being forgotten or rising to glory. The decision should be made by him.

Hours before Guaidó’s January 10 speech, the deputies discussed the so-called “Statute Law that governs the transition.” There was talk of a power vacuum and it was agreed that the president of the National Assembly should assume the powers of the executive. In the discussion, they were the main parties of Parliament – the so-called G4, composed of Primero Justicia, Voluntad Popular, Un Nuevo Tiempo and Acción Democrática – which ended up discarding the document that required Guaidó to assume the presidency. In the end the law was not voted upon because there was a rigid, unbearable tension. It was an unacceptable document for, for example, the so-called Fracción of July 16 (composed of independent deputies, of other parties, and of the political forces Vente Venezuela and Alianza Bravo Pueblo, the parties of María Corina Machado and Antonio Ledezma, respectively) . But there was the law. And the world learned of the danger it posed.

Throughout the afternoon of January 10, those who were aware of the discussion on the Transitional Status Law, presumed that, although it was never approved, Juan Guaidó was subordinating himself to it. As a result, they started making calls.

The discussions took hours. Late at night in a hotel in eastern Caracas, Juan Guaidó was at the center of an argument between the four main Venezuelan leaders behind D-Day. And although all had already drawn up the plans for the operation, two did not take a final position. Meanwhile, Guaidó was being inundated with messages, and one of them stood out. Signed by Secretary General Almagro, it was a very tough letter that put the deputy – or president – between the sword and the wall.

There were several arguments for not embarking on a dangerous path, full of obstacles, and too challenging for some men who, armed with machine guns and bayonets, seemed ready to respond, from their trenches, to the Caribbean invasion of Normandy. He was worried that the democratic world would not automatically recognize Juan Guaidó as the interim president of Venezuela. And, finally, that boldness would end up beheading the Assembly’s leadership and leaving Popular Will out of the institutional game. In the end, that day, he advised: “Let’s make a move, but now with everything at our disposal.”

“I adhere to Articles 233, 333, and 350 of the Constitution to achieve the cessation of the usurpation,” said Juan Guaidó at his speech on January 11 in eastern Caracas. The avenue was full of people and, just when the deputy was climbing onto the platform, the citizens began to chant: “President, president, president, president!”

Not all understood well what the words of Juan Guaidó meant. Whether he was assuming the presidency or not. There was no certainty. The happy ones said yes and the bitter ones, said no. But, minutes later, what many called a miracle appeared, which was to cause the emergence of a new movement around a simple idea.

“We welcome the assumption of Juan Guaidó as interim president of Venezuela, in accordance with Article 233 of the political Constitution. He has our support, that of the international community, and that of the people of Venezuela,” wrote the secretary general of the Organization of American States, Luis Almagro, on the afternoon of January 11.

And we are off! All together with Almagro. He has said it.

Waiting for D Day

The opposition parties, apart from Popular Will and the Julio Borges wing in Primero Justicia – that is, the wing of the former presidential candidate, Henrique Capriles – gave instructions to their militancy: the president of the National Assembly has not assumed anything: you can not call him president of the country. The day after January 11, the youths disobeyed. And in what was to soon mushroom, in each small town hall, the cry was the same: Juan Guaidó is president.

Now what was left was the oath of office. The scaffolding on which the disembarkation would finally take place had already been lifted. The big D-Day blow. But a picture was needed. It was urgent and the citizens asked for it. We must not detract from what María Corina Machado represents today in the struggle against tyranny. Brave, immovable, sometimes too severe. She was the one who, on previous occasions, had been impatient with those whom she deemed to have strayed from the route for freedom. And a large number of Venezuelans wanted to know what she thought about Juan Guaidó and the new historical role he was taking on. They wanted her to express, clearly and publicly, if she supported the young man from Popular Will.

“We have to do whatever it takes to achieve Venezuela’s freedom. Count on me to advance strongly along this route, Juan,” Machado wrote in a tweet that she published on the night of January 12. The opposition leader added a photo in which they are both, sitting on a sofa, relaxed, talking. It got more than twenty thousand likes, and more than thirteen thousand retweets. The next day it appeared in all the networks and in several newspapers. The most important leaders of the Venezuelan opposition had lined up behind him. He was a new phenomenon, imbue with new life. Yes. Now he could be trusted again. Little by little, hope began to be reborn.

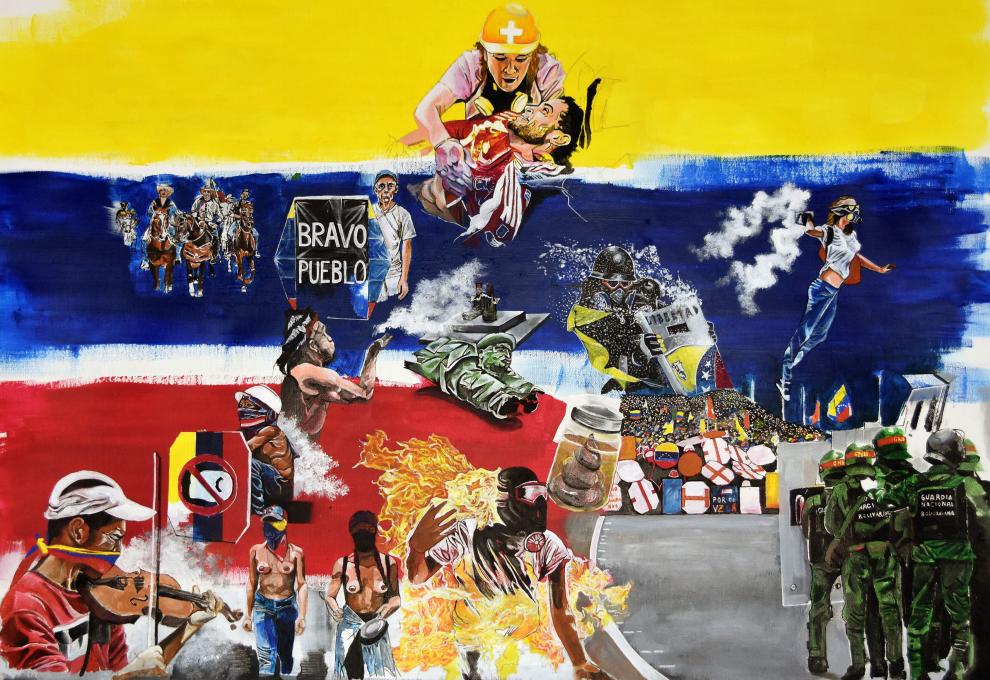

The town councils that were held later were proof of this. Every day, in a different city, thousands of people gathered to honor the bravest young man in politics in a country accustomed to disappointment, timidity, and mediocrity. Although the speech was not explicit, the reality was that Guaidó was challenging the regime as no one had done in years. The mere fact that the others, because he had not yet done so, began to call him president, consisted of the greatest audacity ever seen. The brief cruelty of the dictatorship lasted only a few minutes. On January 13, when Guaidó went to a town hall, officials of the political police of Maduro, the notorious SEBIN, kidnapped him. Then, he was released.

The days passed and a narrative came to light that favored the new opposition leader: that the world supported him, that Nicolás Maduro was barricading himself in with his bandits, that the kidnapping of January 13 was a sign of the crisis among the Chavista officials and that their fall was imminent. That they were nearly there, but something was still missing. The embittered element in the opposition, but those who in some way always proved to be right, requested that President Guaidó formalize his new position through a public act: a swearing in.

From Washington DC the hawks began to plan. In low flight, like vultures on leather, they tormented those who, in their führerbunker, insisted on continuing to organize the war. Sending battalions, picking up platoons and distributing soldiers. As if all was not an illusion. As if the war had not been lost and there were no such battalions, those soldiers and those Panzer divisions.

John Bolton, Mike Pompeo, Mike Pence, and Marco Rubio. Their Twitter feeds must have been a nightmare for Americans who did not understand anything about why these gringos started tweeting in Spanish and about Venezuela, Venezuela. Only Venezuela. Threats to the military, announcement of new sanctions and full support for Juan Guaidó ensued. Meanwhile, one or another defector from the Venezuelan Armed Forces emerged. And, immediately, some American officials emerged to back them. “We support the group of soldiers who are rebelling against Maduro and subordinating themselves to Guaidó,” Rubio wrote on Twitter about uniformed men who, from Colombia, refused to obey Nicolás Maduro.

The debate over the swearing-in intensified. There were more and more people who expressed the urgency for Juan Guaidó to assume the symbols of power. The photo, the raised hand, the words “I swear”, “I am president”, became peremptory. And as there was no clarity, there were still some who, meanwhile, said it again and again: “Juan Guaidó, president-of-the-National Assembly-of-Venezuela”, “Juan Guaidó, the deputy.” And in order not to give room for suspicion, he had to be sworn in.

An agreement in the National Assembly revived tensions. During the session of Tuesday, January 15, the majority of the deputies approved that the powers of executive now corresponded to the National Assembly, plenary session. Nothing from Guaidó. Crazy. Unconstitutional, I agreed.

No surprises, the Faction of the July 16 Movement (Machado and Ledezma) abstained. Some did not understand their position and, then, they reprimanded the deputies of the July 16 Movement. Perhaps, without understanding the danger of this unconstitutional agreement. But something changed on the morning of January 15. At first, the agreement was different. Another text, that had been drawn up precisely to ratify Juan Guaidó as president of Venezuela, ended up in the trash.

The opposition began to press its position. Others, with much greater firepower, such as the United States, deployed – and, in fact, threatened – those alleged opponents who intended to sabotage the process that had already begun. No one was going to prevent the execution of the operation. No one. And whoever tried it, was going to suffer consequences.

More pressure. More meetings. Greater participation of the world. Sources say that Colombia and Brazil were main actors. In the US capital, the diplomat Arria and Senator Rubio talked on January 15. Immediately after the meeting, before the Congress, the young Senator from Florida said that the United States should express its recognition of Guaidó as interim president of Venezuela. The route is the one that marks the fulfillment of Article 233. Period. Juan Guaidó must be sworn in.

The restlessness and tensions within the group of the four Venezuelan leaders led to the need to strengthen – and shield – the strategy. It was time to set limits, time intervals, and deadlines. The new young political star must take responsibility, but everyone believes he will not do so. And that was a key moment.

In Washington DC there were concerns about the apparent lack of determination, of tensions and pressures. You have to remember something: Juan Guaidó is at the center of a dangerous conflict that involves the worst mafias in Venezuela and the world. The pressures and threats are untold. Then, representatives in the Organization of American States decided to talk.

On January 16, the United States delegation convened a meeting between other ambassadors and Juan Guaidó, along with Leopoldo López. The representatives, in the same space, spoke with these Venezuelans who explained what the path forward was. Articles 233, 333, and 350. Guaidó explained how everything was constitutional. And he said, however, that he needed the support of the world to move forward. And part of the world, gathered in that room in Washington DC, guaranteed it.

There were the ambassadors from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Chile, Honduras, Paraguay, and the United States. This last country clarified to Juan Guaidó that, if everything was constitutional, and that he was sure that this route was the right one, that he had all of their support. Onward!

The next day, in Brazil, two historic meetings were held. On the one hand, the president, Jair Bolsonaro, shook hands with the head of the Supreme Court of Justice in exile, Miguel Ángel Martín. On the other, representatives of Venezuelan civil society met with the Brazilian Foreign Minister, Ernesto Araújo. The protagonists said that, the result of both meetings was that Brazil was ready to recognize and give its full support to Juan Guaidó. But the swearing-in act was necessary. In favor of this position were Julio Borges, Antonio Ledezma, Carlos Blanco, and the young people of the Rumbo Libertad, a movement that played a fundamental role.

The pieces were positioned. The ships had sailed. Loaded with soldiers, they were ready to stand on the French beaches and unleash the fury of hundreds of thousands. The date was January 23. Guaidó had already announced it.

As the world began to speak, thousands played an essential role. We must mention Leopoldo López who, from his cell, cultivated relationships with top world leaders. The role of Mayor Antonio Ledezma was paramount; since his flight from Venezuela tireless, and inexhaustible, working with his partner María Corina Machado. Diego Arria, with a voice that is heard throughout the world, that is respected. With prestige gained through experience, he convinced everyone of the danger of living with a narco-state.

Also Asdrúbal Aguiar, with his initiative, IDEA, which impelled the most important ex-presidents of Latin America to become allies of the Venezuelan cause. Julio Borges on a permanent tour. The president of the Supreme Court of Justice in exile, as a legitimate institution that travels the world, spoke clearly and convincingly. There were also thousands, thousands, and thousands of Venezuelans, throughout the world, who never rested. Stubborn activists, also masters of political engineering, who generated enough noise that the countries were obligated to stand in solidarity with their cause. The anonymous heroes. The thousands of anonymous heroes. And Almagro, of course. Mr. Luis Almagro. The great father of the project. The spearhead in the international offensive against the tyranny of Maduro.

With the intention of pressing the opinion that the formal act of swearing was the best thing that Juan Guaidó could do, important world leaders began to express their position in favor of this route. The most prominent voice that was raised was that of the president of Colombia, Iván Duque. In an interview with German media outlet DW on January 21, he said: “What we are waiting for, all the countries of the Lima Group, is that this act [the inauguration of Guaidó as interim president] may have a coating of formality and we all must react in unison.”

D Day was just two days away. The factions, responsible for Operation Venezuelan Overlord, had already agreed to it. Between them there was no nervousness. The four leaders already had the certainty that Juan Guaidó was going to be sworn in. The strategy remained hermetic, yes. The regime, which had sought to be aware of the activities of the youth wing of Voluntad Popular, was confident that, in the end, he was not going to be sworn in. They felt that, on the other hand, that everything was going to be channeled towards an eventual dialogue process – again. And this is also what the rest of the quote-unquote opposition, thought. That opposition that ordered that nobody call the president the president.

The private call of Mike Pence to Juan Guaidó, during the night of January 22, was also key. In that call, Pence assured Guaidó that, if he assumed full power of the presidency of Venezuela, and was sworn in, the United States would recognize him and provide him with all the necessary support. It was the last big push that gave confidence to Juan Guaidó to challenge and surprise, not only the regime, but the supposed opposition that controls an important part of the National Assembly. The D Day wait was over

D Day

The bayonets were loaded, the ships were ready, the troops disembarked. The invasion began.

“Today, January 23,” said Juan Guaidó, “in my capacity as president of the National Assembly, before God, Venezuela, and in respect to my fellow deputies…I swear,” and the people burst euphorically, “to formally assume the competencies of the National executive as president,” and people cried when they heard the word president “in charge of Venezuela.”

“What the hell is going on?” said some opposition leaders in WhatsApp groups, according to the Wall Street Journal. You had to see their faces at that moment. Then, in an interview with AFP, Henrique Capriles confessed: “We did not have this information. It surprised many leaders.”

And so, behind the backs of these leaders and the regime, on January 23, a brave young man of Popular Will, protected by the democratic world and its main actors, millions of Venezuelans abroad, millions of Venezuelans in Venezuela and four pivotal leaders, assumed his responsibility. It became the biggest torpedo that has hit Chavismo in twenty years. The game changer. Guaido became the great man. The one that Venezuela always needed.

From a sense of heavy despair, lodged deep in the soul of each Venezuelan, to the genuine and rational conviction, that the end of Chavismo would be in a matter of hours.

Orlando Avendaño is a PanAm Post reporter and columnist from Venezuela. He studied journalism at the Andrés Bello Catholic University. Twitter Follow @OrlvndoA.

Thanks to Orlando!

This article was first published at the Panampost

https://panampost.com/orlando-avendano/2019/02/12/from-despair-to-guaido-how-the-opposition-took-power-in-venezuela/