Venezuela’s Monetary Madness

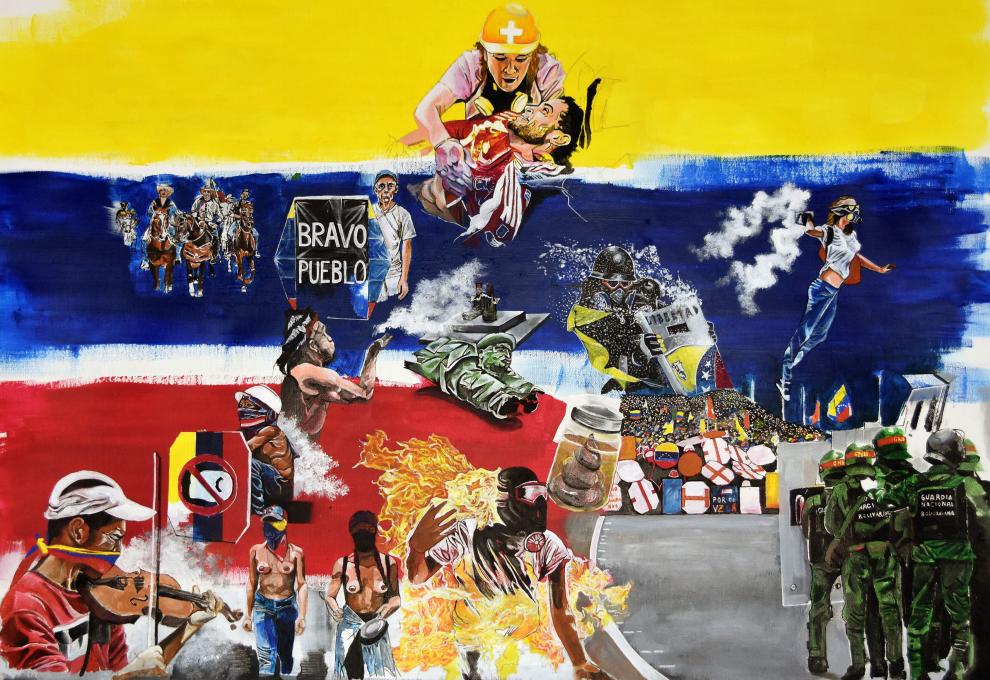

Last month, I wrote an article about Venezuela’s business environment. The country – currently undergoing the biggest humanitarian crisis in Latin America’s history – has one of the least competitive business environments in the world. Among its major economic constraints, the Venezuelan economy suffers from macroeconomic distortions, microeconomic inefficiencies, and hostile policymaking. Together, these constraints have severely deteriorated the profitability and productivity of the Venezuelan private sector. Hence, they have significantly hindered the country’s investment rate, as well as its agricultural and manufacturing output.

Among Venezuela’s macroeconomic distortions, the country has been experiencing elevated levels of monetary instability for years. Since 2013, Venezuela has had the highest inflation rate of any country in the world. Then, since December 2017, Venezuela has been experiencing a phenomenon known as hyperinflation, which is a term that refers to countries having a monthly inflation rate above fifty percent. Overall, the Venezuelan hyperinflationary episode is not just the fourth-longest in history, but among the ones with the highest peak, as the country experienced a one million percent inflation rate in 2018.

Just last week, the Venezuelan government celebrated the eighty-first anniversary of the Venezuelan Central Bank. Normally, central banks are a governmental institution focused on maintaining the monetary stability of their respective economies. Yet, in the case of the Venezuelan Central Bank, its politicization has turned Venezuela into an unprecedented case of monetary madness, so much so that Venezuelans are not even using their domestic currency anymore. So, it only seems fitting that we celebrate the anniversary of the Venezuelan Central Bank by dedicating this week’s column to explaining the typical role of central banks, and how the Venezuelan Central Bank failed its country.

The Purpose of Central Banks

Central banks are institutions created by the state to maintain the monetary stability of an economic area. In this sense, central banks can be national, such as the United States’ Federal Reserve, or supranational, such as the European Central Bank in the Eurozone.

When economists talk about monetary stability, they refer to the financial and price stability of an economy. Regarding financial stability, central banks have to guarantee the proper functioning of the banking sector, which encompasses the intermediation of funds, the management of risks, and the arrangement of payments. They also have to guarantee that the financial system is capable of handling the negative effects of an eventual shock to the economy. For instance, since the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve carries out regular stress testing on banks, a new power given by a financial regulation known as the Dodd-Frank Act.

Regarding price stability, central banks have the mandate to protect the purchasing power of their domestic currency. As such, central banks have a series of tools aimed at maintaining the inflation rate of their economies at about two percent. For instance, central banks use open market operations, which is a term that refers to the buying and selling of government bonds to regulate the supply of money that is on the reserves of banks. Central banks also modify how much money can banks keep on their reserves each night, which is known as the reserve requirement. And lastly, central banks can also modify the economy’s discount rate, which is how much the central bank charges for lending funds during its discount window.

Central banks use these tools to either expand or contract the money supply and therefore, adjust the economy’s inflation rate. Overall, the economics literature agrees about the optimality of having economies with low inflation rates, as price stability enhances investment rates and the efficient allocation of resources. Hence, having a responsible central bank is key to the economic development of nations. In this sense, Robert Barro, an economist at Harvard University, estimates that a 10 percent increase in inflation reduces GDP growth per capita by 0.3 percent.

The Twisted Role of the Venezuelan Central Bank

Originally, the Venezuelan Central Bank was among the most successful in the region. For decades, Venezuela experienced low levels of inflation, capital flights, and financial instability. As such, Venezuela had the highest savings rate of any Latin American nation up until the 1970s.

However, during the Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro presidencies (1998 up to date), the dynamics of the Venezuelan central bank changed fundamentally. In repetitive occasions, the executive branch – in collaboration with its loyal legislative branch and supreme court – promoted a series of laws that took away the political independence of the central bank.

For instance, the government forced the central bank’s technocrats to resign, so they could replace them with people affiliated to the ruling political party. And similarly, the legislative branch would pass laws that enabled the executive branch to manage resources with little to no accountability, such as the creation of the national development fund (FONDEN).

With the politicization of the Venezuelan Central Bank, the institution became a mere political instrument of the ruling party. In other words, the central bank began using its tools not to maintain price and financial stability, but to advance the political agenda of the government. As a result, the central bank allowed the government to incur excessive levels of foreign debt, which currently exceeds 150 billion U.S. dollars—five times the country’s 2018 exports. It also allowed astonishing levels of capital flights, which exceeds 200 billion dollars.

Moreover, the central bank started using monetary policy for political purposes. For instance, the central bank would increase the money supply at the wish of the government. In electoral years, the bank increased the money supply to stimulate the economy in the short-run, so that the increase in economic activity also increases the popularity of the government. This became evident in 2013 when the country’s inflation rate doubled after the country experienced two presidential elections in six months. Then, since oil prices declined, the government would use the central bank to monetize its fiscal deficits, a process that eventually skyrocketed Venezuela’s inflation rate.

The twisted actions of the central bank ended up destroying the value of the Venezuelan currency. From the time Chavez took office up to today, the real exchange rate between an American Dollar and a Venezuelan Bolivar increased exponentially. Today, it takes almost 400 thousand Bolivars to buy an American dollar. And tomorrow, it will certainly take even more bolivars. As a result, an increasing number of Venezuelans are nowadays using dollars in their everyday transactions, a process known as transactional dollarization. According to estimates, over 50 percent of the country’s commercial transactions are now carried in dollars, a process that in some cities reaches over 80 percent of transactions. Hence, in the eighty-first anniversary of the Venezuelan Central Bank, there is nothing to celebrate, as its biggest legacy is the destruction of its own currency, which is quite an accomplishment.

By Jorge Jraissati

Jorge Jraissati is the president of the Venezuelan Alliance. Graduated at the Wilkes Honors College, Jorge is an economist, political leader, and a fellow at the Abigail Adams Institute. Jorge has been invited as a guest lecturer to over 20 universities, such as Harvard, NYU, and Cambridge.